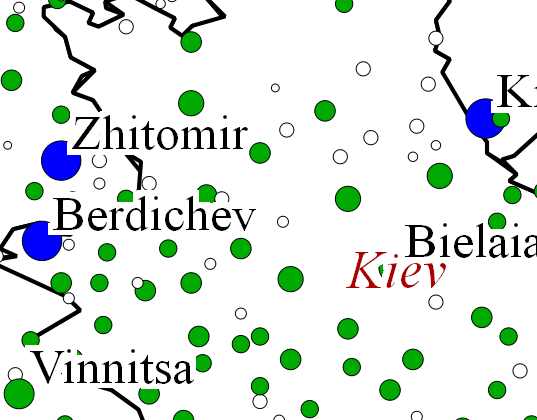

This map shows the precise place of residence of over 4.3 million Jews at the time of the Russian census of 1897.

The census enumerated over 5 million Jews living in the Pale of Settlement, the 25 western provinces of the Russian Empire in which Jews were generally free to reside. Together with the Jewish communities that existed beyond the boundaries of the Pale, the Russian Empire was home to some 5.3 million Jews, more than half of world Jewry. It is the best source of statistical information on this population, and probably on any other large Jewish concentration prior to WWII.

The map represents a new database that was recently created by Gennady Polonetsky and I, mainly from figures published in the 1897 census. It is posted here, along with a few notes, in order to make this visualization of the patterns of Jewish settlement in the Russian Empire available to the interested readers. Other pieces of analysis pertaining to this database will be posted soon.

Things to Note

Dispersion

As opposed to the the 20th Century tendency of Jews to crowd into large metropolitan centers, it appears that the Jews in the Pale have had a very uniform spatial distribution, with a few exceptions that will be noted below. It is almost as if Jewish communities in the Pale were dispersed like an expanding gas within a closed chamber. The best simple answer to the question “where did Jews live?” is roughly “all over the place, as long as they were allowed”. But as we look more closely, it seems that there’s more to it, and a few patterns are discernible.

Areas of New Settlement: New Russia

The four southern provinces bordering with the Black Sea (Bessarabia, Kherson, Ekaterinoslav, and Taurida) were known at that time as the region of New-Russia. New, because it was only fully incorporated into the Russian Empire at the end of the 18th Century. I think that it is useful to think of this region as the Russian equivalent of the American Mid-West, with recently opened vast fertile lands and emerging commercial, industrial, and port cities.

The Russian Tsars sought to settle this area, and in addition to encouraging non-Jewish farmers and townsmen to settle there, it was decided to include it within the Pale of Settlement. This meant that as opposed to the territories of Russia prior to the Polish partitions, New-Russia had opened up as an attractive new destination for Jewish immigration during the 19th Century.

This explains the rather sparse distribution of Jewish communities within that area. However, this sparsity doesn’t necessarily imply that Jews formed a relatively smaller proportion of the total population, as most of the population had only recently settled there, and as Jews tended to live there in larger towns compared to other regions. Indeed, the proportion of Jews in the province of Taurida (Crimea) was relatively small, but that was not the case for the other three provinces.

Areas of New Settlement: Left Bank Ukraine

The provinces of Poltava and Chernigov were situated in Left Bank Ukraine, on the other side of the Dnieper river which marked the eastern border of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Being outside the Polish state and somewhat indirectly (through a Cossack autonomy) under the dominions of the Tsars, Jews did not settle this area prior to the partitions of Poland.

Despite of not being part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Poltava and Chernigov were included within the Pale, and Jews were allowed to settle there during the 19th Century. As opposed to New-Russia, these were already settled lands, so Jewish settlement was new while the non-Jewish population was already established there. This explains both the sparsity of Jewish settlement, and the fact that they did not form more than 4.5% of the total population in Left Bank Ukraine, as opposed to 11% in the Pale as a whole on average.

Courlnad

The province of Courland was situated across the border of the Pale, in the area bounded between the Baltic Sea to the north and to the west, and the province of Kovno to the south. Today this area is part of Latvia. The map shows that Courland stands out as a relatively dense area of Jewish settlement beyond the Pale.

Courland makes a special case in many ways. Prior to the partitions of Poland, Courland was nominally under Polish sovereignty, but effectively it was an autonomous German duchy. Jews did settle Courland prior to the partitions, but it was excluded from the Pale in the early 19th Century. This meant that restrictions were put on new settlement, but the previously established Jewish communities were allowed.

Pripyat Marches

Across the south side of the Province of Minsk, one can see a stripe of land going from west to east which seems to have successfully rejected Jewish settlement. Surrounded from all sides by dense Jewish population, this Jewish-free land demands an explanation.

The answer is that this land had rejected Jews and non-Jews in equal measures. The Pripyat Marches, an area of muddy and often flooded woodlands along the Pripyat River, may well be one of the least inhabitable places in Europe, and that was true even before it became the site of the 1986 Chernobyl Disaster.

How the Database Was Created

Two main sources were used to create the database behind this map. The first is an extensive volume from among the publications of the 1897 census enumerating every locality in the Russian Empire that had at least 500 inhabitants. Tens of thousands of localities were listed in it this volume, and for each locality the volume reported the total town population, the total population of males and of females, the type of the locality, and the district to which it belonged. Importantly, every religious group that formed more than 10% of the total population in the locality was listed and counted.

For every town that had a Jewish community listed, we coded the total population, the size of the Jewish population, the district and the type. The volume did not report the precise geographical location of the locality. Fortunately, the JewishGen Communities Database had the coordinates for most of these towns. Coordinates of other towns had to be spotted using various online resources. This often proved to be a challenging task, given the many changes that the localities names had gone through in the past century.

More than 300 communities were listed on the JewishGen database, but were not listed on the localities volume. Normally, JewishGen reports the size of the Jewish population indirectly from the localities volume (My understanding is that JewishGen used as a source the entries from the Russian Jewish Encyclopedia published between 1906-1913, which in turn had used the localities volume.) These were mostly very small communities and unless there was an alternative source reporting the size of the their populations, these figures remained unknown. They are marked on the map along with the smallest communities as communities of unknown size.

Which Communities Are Included?

A Jewish community was listed in the localities volume if the following two conditions applied:

- The locality had a population of at least 500 inhabitants

- The Jewish population was at least 10% of the total population of the town

Additionally, as mentioned above, there are more than 300 additional communities that were listed on JewishGen Communities Database, but did not list a Jewish population in the localities volume of the census. These are mostly smaller communities and villages, and sometimes, potentially, communities that existed before or after 1897, but not at the time of the census.

Which Communities Are Excluded?

Communities that are not marked on this map belong to one of the following two groups

- Communities in towns that had less than 500 inhabitants

- Communities in towns that had more than 500 inhabitants, but where Jews were less than 10% of the population

My guess is that most of the missing communities within the Pale belong to the first group, and that most of the missing communities beyond the Pale belong to the second.

We can observe towns whose Jewish population was between 10%-20% of the total population, but this is a rare case, most towns had a far greater proportion. It seems unlikely that this pattern is broken as we cross the 10% boundary downwards

On the other hand, beyond the Pale the restrictions on Jewish residence were such that commonly relatively few Jews were able to gather in a few large towns.

Further Reading

I am aware of a single paper that has made extensive use of the data in the localities volume. It was all the more impressive to learn that it was written without using a computerized data file.

Rowland, Richard H. (1986), “Geographical Patterns of the Jewish Population in the Pale of Settlement of Late Nineteenth Century Russia”, Jewish Social Studies 48 (3/4).

Perlmann, Joel (2006), “The Local Geographic Origins of Russian-Jewish Immigrants, Circa 1900”, Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 465.

The JewishGen Communities Database, which was an important source contributing the Shtetlach database, is an excellent database on Jewish communities in the 19th and 20th Century in eastern Europe and other countries. It was designed mainly for genealogical research. It features a Soundex search, links to genealogical sources and maps, alternate names of localities in different languages and periods, and many other useful options.

On the formation of the Pale of Settlement, see John Klier’s entry on the Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, or the detailed account in his fundamental 1986 book.

Acknowledgments

The work on the Shtetlach database was enabled by the invaluable partnership with Gennady Polonetsky. The shapefiles of the provinces of the Russian Empire were created and given to my use by Andre Zerger (CSRIO).

I have benefited from conversations on this topic with Prof. Shaul Stampfer (Hebrew University), and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern (Northwestern University).

Leave a comment