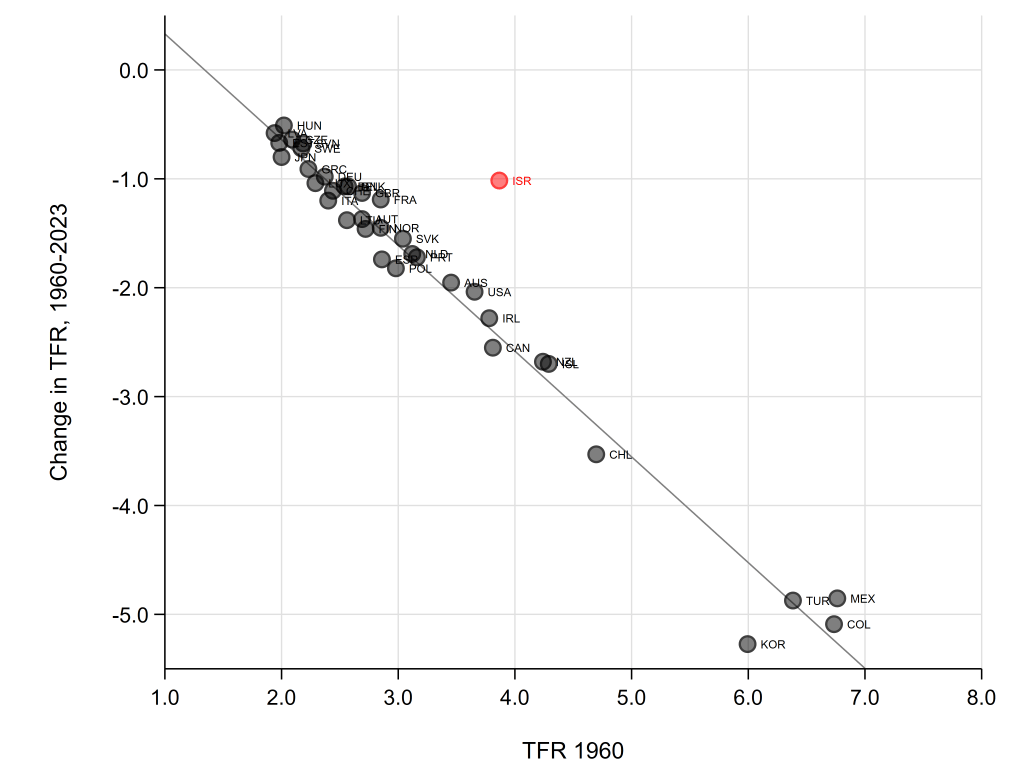

Israel’s extreme demographic exceptionalism can be summarized in the following figure:

Each point in the chart represents one of the OECD countries, a group commonly used as a reference for Israel in socio-economic comparisons. Along the horizontal axis, the countries are ordered by their total fertility rate (TFR) in 1960.

The TFR is the standard measure of population fertility. It answers the following question: how many children, on average, is a woman expected to have over her lifetime, assuming that at each age the probability of giving birth remains equal to the current probability observed among women of that age. As the chart shows, in 1960 Israel’s TFR was 3.87—meaning that, on average, each woman was expected to have nearly four children. This was higher than fertility levels in Europe, but very similar to those prevailing in most Anglosphere countries: Australia, Ireland, the United States, New Zealand, and Canada. In any case, at the end of the baby-boom era, Israel was not exceptional.

From that point onward, all OECD countries experienced convergence toward very low fertility levels. First, the average TFR fell from 3.25 in 1960 to 1.95 in 1990, and then to 1.44 in 2023. The replacement-level fertility—the fertility rate at which a population replaces itself, in the sense that each generation produces the same number of offspring—is 2.1. On average, OECD countries fell below replacement level already by the late 1980s, and since then fertility has continued to decline to historically unprecedented lows. Today, all OECD countries are below this threshold, many far below it, meaning that each generation everywhere produces fewer children than the previous one. The most extreme case is South Korea, where the TFR has fallen below 1 (0.72 in 2023). This phenomenon is known in the literature as the “second demographic transition.”

There is one exception to this pattern: Israel.

An animated version of the same data illustrates how this process unfolded. In this moving figure, the TFR in any given year is plotted against the TFR in 1960. Convergence is manifested in the declining dispersion along the vertical axis, all countries move toward a TFR clustered tightly around 1.3. All, except for Israel.

As of 2023, Israel’s TFR stood at 2.85. A distant second among OECD countries was Mexico, at 1.9. Israel was 4.5(!) standard deviations above the OECD mean. This outcome is indeed influenced by very high fertility among the ultra-Orthodox population, and until a few years ago also among Muslim women. However, secular Jews have also come to stand out relative to their peers in other countries.

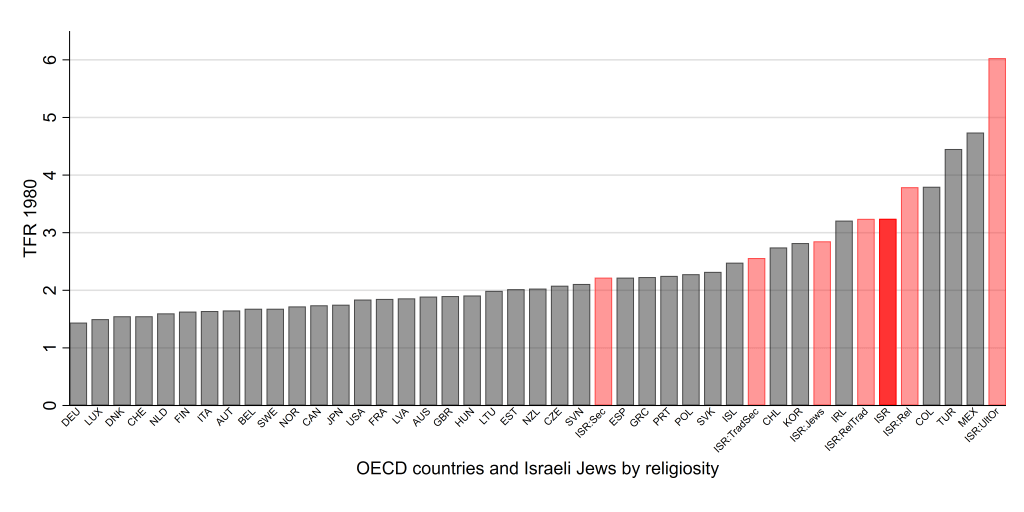

This can be seen in the following two figures, which are based on data going back to 1980 and distinguish TFR by degree of religiosity among Israeli Jews (secular, traditional–secular, traditional–religious, religious, and ultra-Orthodox). In 1980 (more precisely, 1979–1981), the TFR of secular Israeli Jews was similar to that of countries such as Greece, Spain, Portugal, and New Zealand, and well below that of Ireland.

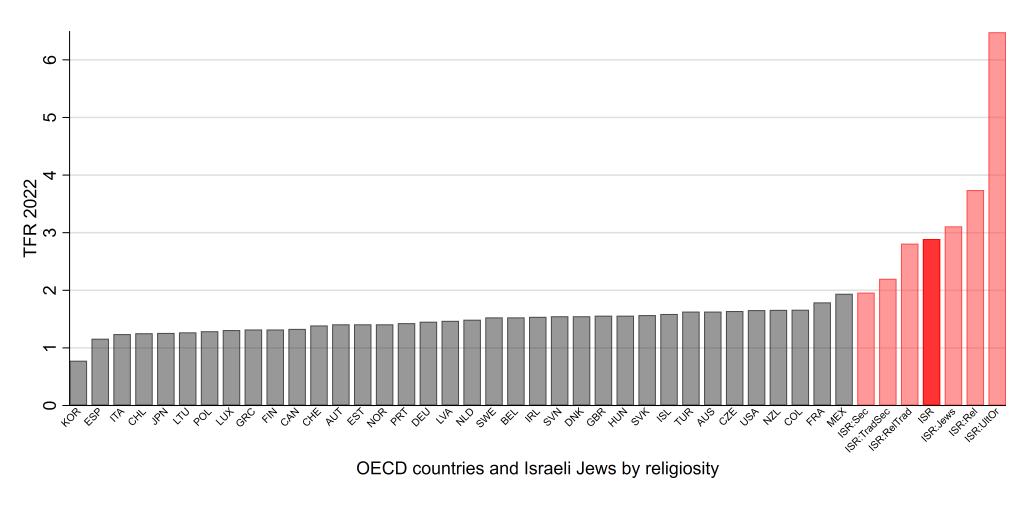

According to the most recent data (2021–2023), Israel would still lead the OECD even if its entire population were Jewish and secular.

However, the exceptional nature of Israel’s demographic trends is twofold and does not consist solely in remaining well above replacement level. To see this, consider the vertical axis in Figure 1, which shows the change in TFR between 1960 and 2023. The first striking fact is that almost all OECD countries lie close to a single downward-sloping curve. That is, the higher a country’s fertility level was in 1960, the more sharply it declined over the subsequent 63 years. This pattern implies that the Western world experienced downward convergence in fertility rates: not only did fertility fall sharply, it also became increasingly similar across countries. Notably, the slope of this curve is close to −1 and not statistically distinguishable from it. Were the slope exactly −1, all countries would have converged toward the same fertility level, and today’s cross-country variation would reflect no historical differences.

Israel, marked in red, is the only country that deviates clearly from this trend line. Based on its fertility level in 1960, a simple projection would predict that by 2023 Israel’s TFR should have fallen by 2.40 births. In reality, it declined by only 1.02. That is, the predicted TFR was 1.46—almost half of its actual current level. Israeli women are having 1.38 more children than expected. As the chart shows, this deviation is unparalleled, though South Korea can also be noted as a case of significant deviation in the opposite direction, albeit smaller in absolute magnitude than Israel’s.

Underlying the second demographic transition is, to a large extent, the trend toward later ages at first birth. As a result, women have fewer children over their lifetimes, and the TFR declines. Indeed, in Israel too women are giving birth at later ages than in the past. Between 1994 and 2016, the average age at first birth among Jewish women increased by nearly three years. But unlike the rest of the Western world, non-religious Jewish women did not significantly reduce their TFR, and for a long period it even rose modestly (fertility among ultra-Orthodox women, by contrast, has declined quite rapidly in recent years). As a result—also due to the growing share of the ultra-Orthodox population—overall fertility in Israel stopped declining, and the current TFR is identical to its level in the early 1990s.

This is a puzzling phenomenon. Non-religious Israeli women delay childbearing by many years, but unlike their counterparts elsewhere in the Western world they do not end up having fewer children.

This phenomenon was recently examined in a paper by demographer Alex Weinreb, “Israel 2025: A Demographic Crossroads,” published as part of the Taub Center’s annual State of the Nation Report. He examines how the number of children already born to non-religious Jewish women aged 30–34 has changed over time. In 2004, the average woman in this age group had already given birth to 1.42 children; in 2019 the number fell to 1.17, and by 2024 it had dropped to 0.87—a total decline of more than half a child on average. So how is it possible that the TFR of these women did not fall accordingly? The answer is that fertility at older ages increased substantially. These births did not disappear; they were postponed. Until recently, the postponement was one-for-one: for each birth that disappeared at younger ages, roughly one additional birth appeared at older ages—35–39 and even 40–44. This is a remarkable phenomenon, especially given that nothing similar has occurred in any other Western country.

Weinreb shows that the trend of delayed childbearing continues. The question, then, is whether this postponement will continue as before, such that completed fertility among non-religious Jewish women will remain high.

His answer is no.

This conclusion is based on a statistical forecast extrapolating past trends, but at its core the explanation is simple: there is a limit to how much childbearing can be postponed. One can delay births from age 25 to 30, and then from 30 to 35. But as one approaches age 40—and certainly beyond—biological constraints become binding. There is nowhere left to postpone.

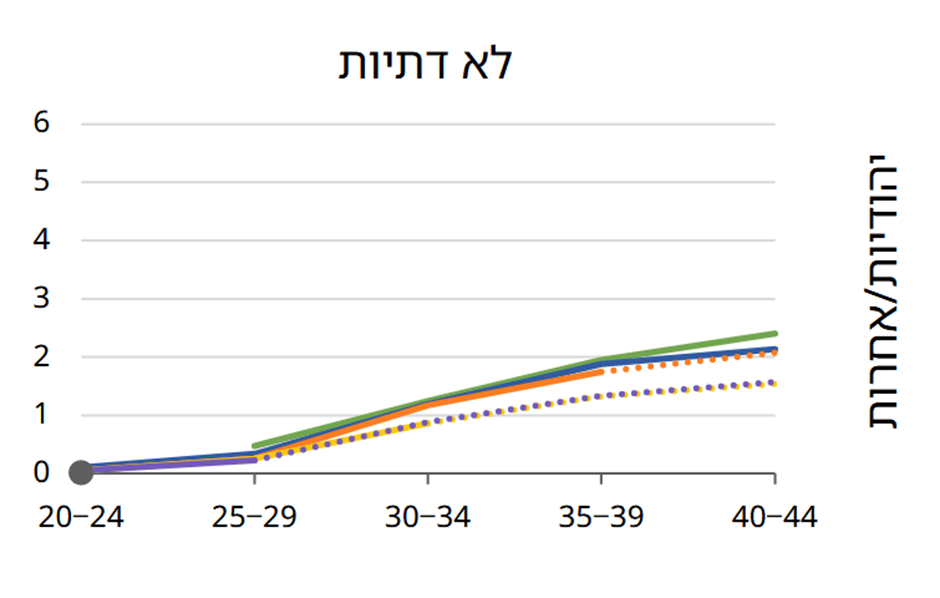

This forecast is illustrated in Figure 4, taken from Weinreb’s paper. The two most recent cohorts of non-religious women for whom near-complete fertility data are available are those who reached ages 40–44 in 2019 (green) and in 2024 (blue). Their average number of children was just over two in both cases. The next cohort, which will reach those ages in 2029 (orange), is also expected to have two children by then (the dashed line indicates a projection based on trend extrapolation rather than observed data). But subsequent cohorts—those currently aged 25–34, who will complete their reproductive years in 2034 and 2039 (yellow and purple)—are expected to have only about 1.5 children on average. They will have postponed childbearing even further, and will be unable to make up the shortfall.

In other words, with a long delay, and unless fertility trends change dramatically, non-religious Jewish women are expected over the next decade to experience the second demographic transition that their counterparts throughout the Western world went through several decades ago. Their completed fertility will fall well below replacement level.

The common explanation for Israel’s high fertility is the existence of traditional norms that encourage a special preference and appreciation among Jews—even secular ones—for large families with many children. But the trends described above cast serious doubt on such an explanation, at least in its simplistic version. After all, no one claims that these social norms are new; they are usually attributed to the continuation of an ancient tradition. Yet if Jews had a strong preference for large families already in 1960, that preference was no different from that of Americans, Canadians, Australians, Irish, and New Zealanders, whose fertility rates at the time were similar to Israel’s. The crucial point is that Israel’s fertility patterns became exceptional only in the last decades of the twentieth century. A full explanation cannot rely solely on long-standing traditions; it must explain why, unlike in every other Western country, this tradition did not break—why completed fertility norms changed very slowly between 1960 and 1990, and then remained essentially unchanged for more than three decades thereafter.

Today, as noted, Israel stands at a demographic crossroads. Whether it will become “a nation like all others,” or continue—demographically—to dwell apart, though somewhat less so than in the past, remains an open question. Among other things, the answer depends on future fertility trends in the ultra-Orthodox community: whether the rapid decline in fertility among ultra-Orthodox women marks the beginning of a demographic transition in that sector as well, or whether, in the more distant future, most of Israel’s population will be ultra-Orthodox and overall fertility rates will once again rise.

Leave a comment