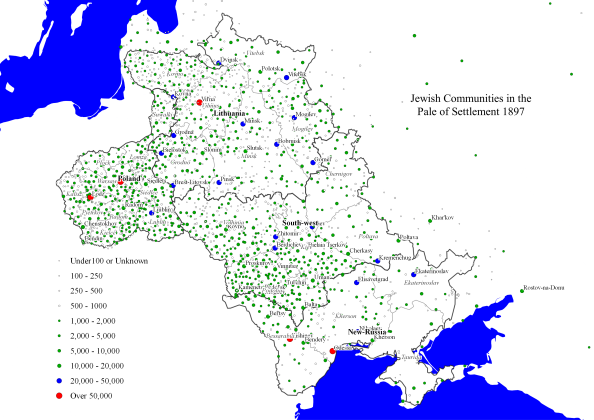

This map shows the precise place of residence of over 4.3 million Jews at the time of the Russian census of 1897.

The census enumerated over 5 million Jews living in the Pale of Settlement, the 25 western provinces of the Russian Empire in which Jews were generally free to reside. Together with the Jewish communities that existed beyond the boundaries of the Pale, the Russian Empire was home to some 5.3 million Jews, more than half of world Jewry. It is the best source of statistical information on this population, and probably on any other large Jewish concentration prior to WWII.

The map represents a new database that was recently created by Gennady Polonetsky and I, mainly from figures published in the 1897 census. It is posted here, along with a few notes, in order to make this visualization of the patterns of Jewish settlement in the Russian Empire available to the interested readers. Other pieces of analysis pertaining to this database will be posted soon.

Things to Note

Dispersion

As opposed to the the 20th Century tendency of Jews to crowd into large metropolitan centers, it appears that the Jews in the Pale have had a very uniform spatial distribution, with a few exceptions that will be noted below. It is almost as if Jewish communities in the Pale were dispersed like an expanding gas within a closed chamber. The best simple answer to the question “where did Jews live?” is roughly “all over the place, as long as they were allowed”. But as we look more closely, it seems that there’s more to it, and a few patterns are discernible.

Areas of New Settlement: New Russia

The four southern provinces bordering with the Black Sea (Bessarabia, Kherson, Ekaterinoslav, and Taurida) were known at that time as the region of New-Russia. New, because it was only fully incorporated into the Russian Empire at the end of the 18th Century. I think that it is useful to think of this region as the Russian equivalent of the American Mid-West, with recently opened vast fertile lands and emerging commercial, industrial, and port cities.

The Russian Tsars sought to settle this area, and in addition to encouraging non-Jewish farmers and townsmen to settle there, it was decided to include it within the Pale of Settlement. This meant that as opposed to the territories of Russia prior to the Polish partitions, New-Russia had opened up as an attractive new destination for Jewish immigration during the 19th Century.

This explains the rather sparse distribution of Jewish communities within that area. However, this sparsity doesn’t necessarily imply that Jews formed a relatively smaller proportion of the total population, as most of the population had only recently settled there, and as Jews tended to live there in larger towns compared to other regions. Indeed, the proportion of Jews in the province of Taurida (Crimea) was relatively small, but that was not the case for the other three provinces.

Areas of New Settlement: Left Bank Ukraine

The provinces of Poltava and Chernigov were situated in Left Bank Ukraine, on the other side of the Dnieper river which marked the eastern border of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Being outside the Polish state and somewhat indirectly (through a Cossack autonomy) under the dominions of the Tsars, Jews did not settle this area prior to the partitions of Poland.

Despite of not being part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Poltava and Chernigov were included within the Pale, and Jews were allowed to settle there during the 19th Century. As opposed to New-Russia, these were already settled lands, so Jewish settlement was new while the non-Jewish population was already established there. This explains both the sparsity of Jewish settlement, and the fact that they did not form more than 4.5% of the total population in Left Bank Ukraine, as opposed to 11% in the Pale as a whole on average.

Courlnad

The province of Courland was situated across the border of the Pale, in the area bounded between the Baltic Sea to the north and to the west, and the province of Kovno to the south. Today this area is part of Latvia. The map shows that Courland stands out as a relatively dense area of Jewish settlement beyond the Pale.

Courland makes a special case in many ways. Prior to the partitions of Poland, Courland was nominally under Polish sovereignty, but effectively it was an autonomous German duchy. Jews did settle Courland prior to the partitions, but it was excluded from the Pale in the early 19th Century. This meant that restrictions were put on new settlement, but the previously established Jewish communities were allowed.

Pripyat Marches

Across the south side of the Province of Minsk, one can see a stripe of land going from west to east which seems to have successfully rejected Jewish settlement. Surrounded from all sides by dense Jewish population, this Jewish-free land demands an explanation.

The answer is that this land had rejected Jews and non-Jews in equal measures. The Pripyat Marches, an area of muddy and often flooded woodlands along the Pripyat River, may well be one of the least inhabitable places in Europe, and that was true even before it became the site of the 1986 Chernobyl Disaster.

How the Database Was Created

Two main sources were used to create the database behind this map. The first is an extensive volume from among the publications of the 1897 census enumerating every locality in the Russian Empire that had at least 500 inhabitants. Tens of thousands of localities were listed in it this volume, and for each locality the volume reported the total town population, the total population of males and of females, the type of the locality, and the district to which it belonged. Importantly, every religious group that formed more than 10% of the total population in the locality was listed and counted.

For every town that had a Jewish community listed, we coded the total population, the size of the Jewish population, the district and the type. The volume did not report the precise geographical location of the locality. Fortunately, the JewishGen Communities Database had the coordinates for most of these towns. Coordinates of other towns had to be spotted using various online resources. This often proved to be a challenging task, given the many changes that the localities names had gone through in the past century.

More than 300 communities were listed on the JewishGen database, but were not listed on the localities volume. Normally, JewishGen reports the size of the Jewish population indirectly from the localities volume (My understanding is that JewishGen used as a source the entries from the Russian Jewish Encyclopedia published between 1906-1913, which in turn had used the localities volume.) These were mostly very small communities and unless there was an alternative source reporting the size of the their populations, these figures remained unknown. They are marked on the map along with the smallest communities as communities of unknown size.

Which Communities Are Included?

A Jewish community was listed in the localities volume if the following two conditions applied:

- The locality had a population of at least 500 inhabitants

- The Jewish population was at least 10% of the total population of the town

Additionally, as mentioned above, there are more than 300 additional communities that were listed on JewishGen Communities Database, but did not list a Jewish population in the localities volume of the census. These are mostly smaller communities and villages, and sometimes, potentially, communities that existed before or after 1897, but not at the time of the census.

Which Communities Are Excluded?

Communities that are not marked on this map belong to one of the following two groups

- Communities in towns that had less than 500 inhabitants

- Communities in towns that had more than 500 inhabitants, but where Jews were less than 10% of the population

My guess is that most of the missing communities within the Pale belong to the first group, and that most of the missing communities beyond the Pale belong to the second.

We can observe towns whose Jewish population was between 10%-20% of the total population, but this is a rare case, most towns had a far greater proportion. It seems unlikely that this pattern is broken as we cross the 10% boundary downwards

On the other hand, beyond the Pale the restrictions on Jewish residence were such that commonly relatively few Jews were able to gather in a few large towns.

Further Reading

I am aware of a single paper that has made extensive use of the data in the localities volume. It was all the more impressive to learn that it was written without using a computerized data file.

Rowland, Richard H. (1986), “Geographical Patterns of the Jewish Population in the Pale of Settlement of Late Nineteenth Century Russia”, Jewish Social Studies 48 (3/4).

Perlmann, Joel (2006), “The Local Geographic Origins of Russian-Jewish Immigrants, Circa 1900”, Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 465.

The JewishGen Communities Database, which was an important source contributing the Shtetlach database, is an excellent database on Jewish communities in the 19th and 20th Century in eastern Europe and other countries. It was designed mainly for genealogical research. It features a Soundex search, links to genealogical sources and maps, alternate names of localities in different languages and periods, and many other useful options.

On the formation of the Pale of Settlement, see John Klier’s entry on the Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, or the detailed account in his fundamental 1986 book.

Acknowledgments

The work on the Shtetlach database was enabled by the invaluable partnership with Gennady Polonetsky. The shapefiles of the provinces of the Russian Empire were created and given to my use by Andre Zerger (CSRIO).

I have benefited from conversations on this topic with Prof. Shaul Stampfer (Hebrew University), and Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern (Northwestern University).

Karen Amato

March 24, 2016

Hello. I am trying to find the name of my ancestors’ town in the former Russia, noted in the US 1930 Census as something like Bellatsko or Billatsko. They left around 1898. I have searched, but cannot find it. I believe the family lived near Kiev and/or Chernobyl. I found your map, but don’t know how to use it (which perhaps dates me…) Are you able to find s town that resembles this name? Thank you, Karen

Yannay Spitzer

March 24, 2016

Karen,

I was unable to find a town in Kiev province with a name closely resembling this. I understand that you have a very fuzzy transliteration of the name of the town from the census (I looked at the scans, and I would agree with your transliteration).

If you know from another reliable source of information that this place should be around Kiev, then my best guess is that this was Biala Tserkov (see on JewishGen: http://data.jewishgen.org/wconnect/wc.dll?jg~jgsys~community~-1035624), which was a fairly large town that is labeled on the map that I produced.

However, if the proximity to Chernobyl is certain, then that probably wasn’t it, as Kiev is closer to BTs than Chernobyl.

I hope this helped…

Yannay

Jill

April 26, 2016

Hi. According to a US WWI registration card, my ancestor was born in “Bohky, Russia”. In various US census reports, I have seen his place of birth listed as “Russia” and “Russia Poland”, leading me to believe that he was born in the Polish area of the Pale Settlement; however, I cannot figure out what town “Bohky” actually is. Any help would be appreciated, thanks!

Yannay Spitzer

April 27, 2016

Jill,

I am guessing that there’s a transliteration error in the document. The “h” almost surely isn’t correct, and probably other letters in the interior of the place name. Do you have a scanned image of the document? Perhaps I’ll able to give a more educated shot at this puzzle.

Yannay

Jill

April 28, 2016

Hi Yannay,

The scanned image very clearly says “Bohky”. However, I was just doing a lot of exploring on the Ellis Island website, and while I could not find the name I am familiar with for my ancestor, I did find several people with a similarly spelled last name to his who arrived around when he did, and are listed as coming from “Bocki”, “Bransk”, “Backy”, “Boske”, and “Bille”. I started looking into these names and came up with “Boćki, Poland”. I have a feeling that this might be the right town. I am also hoping that some of my father’s cousins have more information, and maybe can confirm. Thanks for your help!

Yannay Spitzer

April 29, 2016

That’s got to be it, Bransk is simply the nearby town, and there’s no wonder that immigrants of the same extended family came from both places. My guess regarding the misspelling of your ancestor’s place of origin is that it was copied at a certain point from an unclear handwritten document, and that’s how “ock” became “ohk”. Good luck in your searches!

Jill

May 1, 2016

Okay, now I have another puzzle. On a WWI registration card for a different ancestor it lists place of birth as “Kashuwatt, Russia” (which doesn’t seem to exist). I found him on a census record that states he’s from “Kiev”, so I’m assuming this town is within the Kiev region, but I am not sure what it is. Any ideas? Thanks again!

bessarabianclues

October 20, 2016

Hi, Do you know is there is a Shtetl by the the Name Zaicani or something like that? I would appreciate your aswer. Thank you in advance!

Yvette Merzbacher

Yannay Spitzer

October 23, 2016

Yvette,

In a brief search, I was unable to find any town with this name or one similar to it in Bessarabia. Is the town supposed to be there or elsewhere?

If so, try Saukenai, or let me know if you know what is the region, province, or nearest larger town.

Yannay

bessarabianclues

October 23, 2016

The Region is in Hothyn, near actual Edinets or Yedinitz. Maybe it is mispelt??? There is a place like this near Edinets…

Yannay Spitzer

October 25, 2016

Yvette,

It seems that this place you’ve mentioned is a small village, indeed not far from Yedinets/Edinet.

It does not appear on the volume of the Russian census of 1897 that lists all localities above 500 inhabitatns, and therefore it must have been a small place and I cannot tell whether there were Jews listed there.

Below are links that will direct you to the place:

Yannay

bessarabianclues

October 25, 2016

Thank you. Maybe it was the beginning and there were only a few of them .It Looks like my grandfather either was Born there or might have moved there when he was younger. I will Keep you posted. If in the meantime you see something, please don´t hesitate to write me.

Yvette

Vlad

October 25, 2017

My ex is from Edentzy. Born, grew up and left at age of 20. I just asked her. The only thing she knows is that Hotin is pretty far from Edentzy.

bessarabianclues

October 31, 2017

Thank you so much for your comment. I found out Zaicani is close to Edinets.

Richard Abbott

March 7, 2017

I know from my mother that her mother, Manya Braginsky (maiden name) and her husband, David Isenberg, lived Poltava at the turn of the 20th century. My mother’s oldest sister was born there in 1903. I know there were pogroms during these times, and David left on his own and got to Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, where he worked for 10 years and sent the money back to Manya to pay for her escape/passage. She escaped during a pogrom barely with her life and baby. This information comes from Manya to my mother.

Yannay Spitzer

March 7, 2017

Thanks Richard, this is very interesting. Indeed this area of the Ukraine has seen many pogroms, both in 1905 and during the Russian Civil War. Did your grandmother then leave during the 1905 pogroms or during the latter wave?

Jerry Orland

March 12, 2017

My mother’s naturalization papers state that she was born in Polin, Russia in 1914. Have been attempting to track this town down, but having no luck. Was wondering if you know if it’s a real place. We believe that it’s just outside Moscow, but have no other information. Thank you.

Yannay Spitzer

March 13, 2017

Looking at JewishGen’s communities search page yields nothing. Neither is there such place in Moscow province in the volume of the 1897 census that lists all localities that are greater than 500 inhabitants. The closest is a village or a very small town named Polyano, but I doubt that your mother was born there as all but one of the inhabitants were written as Pravoslav.

I can make a guess: Polin in Yiddish (and Hebrew) is Poland. Could it be that your mother meant that she was born in Poland, Russia? At that time, most of Poland was part of the Russian Empire, and I often see that the place of origin is written as “Poland, Russia”. If you know as a matter of fact that your mother grew up around Moscow, could it be that her family moved there from Poland in the early 1920s? This was the case for hundreds of thousands of Jews who migrated inward to Russia when the restrictions of the Pale of Settlement were removed.

Jerry Orland

May 4, 2017

A relative just told me it was outside Minsk

Vlad

October 25, 2017

I was born and grew up in Moscow. Never heard the name. I don’t think there were too many Jews in Moscow in 1914. It was quite uncommon. Only few rich businessmen were permitted.. And not right outside of Moscow. The absolute majority was in Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. My parents moved to Moscow in 1930’s and 50’s.

John

July 25, 2017

Hi, I’m trying to find the name of my ancestors’ town. In my great-great-grandfather’s marriage act it says he is from “Czimiruk, Caucasus”. I know they were Russian jews, but I can’t find that place. Can someone give me a hand? Thanks!

Yannay Spitzer

July 26, 2017

Dear John,

How much do you trust the correct transcription? If this comes from a difficult handwriting, this may be a short hand for Chernomorsk, currently known as Novorossiysk.

Yannay

John

July 27, 2017

I don’t trust translations, so maybe it could be that place. Was it a jewish settlement? In my great-great-great-grandfather’s death certificate, which is in German because he died in Berlin just before his family came to Argentina, says that he is from somewhere called “Aleksandrovsk”, but there are a lot of places with similar names in Russia and the handwriting is very difficult. Do you know if there’s any jewish settlement with that name? Thank you for your reply!

Yannay Spitzer

July 27, 2017

Chernomorsk did have a Jewish community of 980 people. It was outside of the Pale of Settlement, but that has got to be the case since your source says it was the Caucasus. There a couple of significant Jewish communities in towns called Aleksandrovsk. If you know the region, that is likely to nail it down. One is in Lithuania, in Kovno Province. The largest one was a district capital near Ekaterinoslav, in New Russia.

John

July 27, 2017

I have a death certificate with a very difficult handwriting to understand. The only thing I could understand was “Aleksandrovsk”. Plus, it’s in German, a language I understand but with that handwrite is almost impossible! I just know they were Russian Jews from the caucasus, but in the Ukrainian side. They were non-practicing jews, and my great-great-great-grandfather was a Russian Orthodox priest, until the church learnt he was a Jew and fired him, and he Germanized their surname, so it’s getting very hard for me to do a serious research.

Thank you again for your help, Yannay!

Vlad

October 25, 2017

I’m Russia Jew . Born and grew up there.Couple of points. All the regions you are talking about in Caucasus were mostly populated by Cossacks. Not the friendliest to Jews individuals.

If someone become Russian Orthodox priest it means he was not non-practicing Jew but official convert. At that point in history there was almost no atheists or agnostics. Ether you were a Jewish faith with all consequences or Christian that had all the same rights as ethnic Russian folk. So sorry to tell you your grandpa was not a Jew. That simple. A lot of Russian Jews have Germanized last names. Majority of Ashkenazim came from there(Germany) We speak German dialect based language..

There is Alexandrovsk in Ukraine.

Vlad

October 25, 2017

Just one more thing. He could of been cantonist. Caucasus always had a lot of Russian army presence.

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/cantonists

Yannay Spitzer

October 26, 2017

John, I’m sorry, I missed answering your question earlier and only noticed it again now following Vlad’s comment.

I also think that that the case of a Jewish priest is, to say the least, peculiar. There were tens of thousands of Jewish converts to Christianity throughout the 19th century. Many were cantonists (lifelong soldiers recruited at an early age), and others did it for convenience to climb up the the social-economic ladder or to have the residential restrictions removed outside the Pale. The 1897 census does list Jews (e.g., Yiddish as mother tongue) whose occupation is “Christian clergyman”. It is not clear to me how many of these cases are just an error in the census and if not, how many turned Catholic or Lutheran and not Orthodox. Another remote possibility is that he was a Subbotnik of some sort, a Judaizing Orthodox.

You can find Alexandrovsk (currently Zaporizhzhya) here: https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/community.php?usbgn=-1060168

Jill

February 9, 2018

A WWI registration card I believe belongs to my great grandfather lists his place of birth as “Chuskov Russia”. He was born in 1887 or 1888. Any ideas where this may be? Also, a WWI registration card of another relative born around 1890 lists his birthplace as “Kashuwatt, Russia” (which doesn’t seem to exist). I found him on a census record that states he’s from “Kiev”, so I’m assuming this town is within the Kiev region, but I am not sure what it is. Any ideas? Thanks!

Michael Levin

August 1, 2018

“Other pieces of analysis pertaining to this database will be posted soon”. Where can I find more details about this database?

Yannay Spitzer

August 2, 2018

Michael, since I’ve written this post I wrote a paper that makes extensive use of these data. You can find it here: https://yannayspitzer.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/paleincomparison_170209.pdf

Another post describes some aspects of that paper: https://yannayspitzer.net/2015/06/01/a-jewish-russian-frontier-man/

Yannay

Victoria Bronstein

August 4, 2018

My grandfather was born in 1896, when he was naturalised as a South African he transliterated his place of birth as Vishniovec, Poland. Do you know where this is? Thank you

Yannay Spitzer

August 5, 2018

Yes, of course. You can find details on this town on its JewishGen webpage: https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/community.php?usbgn=-1058362

In particular, see: https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/vishnevets/vishnevets.html

Nathan T

August 15, 2018

Hello Dr. Spitzer, I recently came across an immigration document in which my Great-Great Grandfather traveled by ship from Hamburg, Germany to New York City in 1899. I do know that he was Russian, as it says on the document, and that he is from a city that appears to say “Honodok,” but I am not sure, and would really like to know! I’d be glad to offer you an image if you’d like. Thank you!

Nathan T

August 15, 2018

In addition, according to another document, his place of birth is Gallastock, Russia

Yannay Spitzer

August 16, 2018

Nathan,

The first name must be Horodok, and the second must be Bialystok.

There are a number of shtetls whose name is of a similar derivation, but a very safe bet is to assume that we are talking about Grodek, currently in Poland (see here: https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/community.php?usbgn=-503535).

Although there are other towns whose proper name is actually Horodok, Grodek’s Yiddish pronunciation is Horodok and it is the only one of these shtetls in proximity to Bialystok (22 mi.). It is reasonable to believe that your g.g. grandfather wrote Bialystok either because this was the next large city, or because he actually did spend time there before moving overseas.

If you are in doubt, I suggest looking at the other possible matches by searching the JewishGen community data base (https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/Search.asp) for Horodok. You will see 8 other shtetls with the same name derivation.

Nathan T

August 16, 2018

Dr. Spitzer,

Yes, you’re absolutely correct; I was able to determine his place of residence as Horodok, and I am aware that he and his family spoke Hebrew, which would certainly indicate his proximity to Bialystok (as apparently this Horodok had a Hebrew translation, as well, unlike the others). I very much appreciate your assistance!

Vivian

January 11, 2019

You mention a database for the creation of the map. I’m looking for information on the demographics of the shtetl of Stavyshche in the Kyev region near Bila Tserkva. I am the creator of the JewishGen KehilaLinks site for Stavyshche and would like to add the actual numbers from the 1897 census to the updated website, which is in progress. Thank you.

Yannay Spitzer

January 11, 2019

Vivian, the figures for Stavyshche are 3,917 Jews, out of a total population of 8,186

Abigail Kanter Jaye

January 22, 2021

Hell Yannay, Thank you for this research. I am trying to find my maternal grandmother’s town. She called it “Krinke” or Krinker” but these are phonetic spellings — I don’t know the actual spelling. Her maiden name was Cutler, and her father had a tannery/hides business. My maternal grandfather’s name was Prudowsky. He ran away to avoid conscription into what I believe was the Tsar’s army in the early 1900s. My mother was born in New York in 1919, so it’s likely my grandmother emigrated sometime around 1910.

Yannay Spitzer

January 22, 2021

Abigail, this was probably Krynki, currently in Poland near the border with Belarus. Back then it was Grodno province in the Russian Empire, and the nearest large towns were Bialystok and Grodno.

During the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5) many Jewish men worried about being called for the reserves, and preferred to expedite their migration, often without the legally required passport for exiting Russia. Perhaps your great-grandfather was one of them.

See here: https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/community.php?usbgn=-511203

Chim C

February 24, 2021

I am looking at my great grandfather’s immigration docs and its lists Cadan, Russia as of the early 1900’s as his place of origin. I am having trouble tracking it down as it seems there are a number of similar places. Any thoughts on which town this might be?

Yannay Spitzer

February 24, 2021

I think that there is one possibility that stands out: Keydany (in Yiddish Keidan), a Lithuanian town just 27 miles north of Kovno. Does this make sense? If not, please post more details (region, nearby town, etc.).

https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/community.php?usbgn=-2615471

Jill

March 9, 2021

Hi Dr. Spitzer,

A WWI registration card I believe belongs to my great grandfather lists his place of birth as “Chuskov Russia”. He was born in 1887 or 1888. Any ideas where this may be? Also, a WWI registration card of another relative born around 1890 lists his birthplace as “Kashuwatt, Russia” (which doesn’t seem to exist). I found him on a census record that states he’s from “Kiev”, so I’m assuming this town is within the Kiev region, but I am not sure what it is. Any ideas? Thanks!

Yannay Spitzer

March 9, 2021

This town was probably Koshevata (sometimes spelled with a “v” before the “sh”, currently Kivshovata, in the Ukraine). According to JewishGen’s database the Yiddish pronunciation was something like Koshevateh (קאָשעוואַטע). It is not very close to Kiev, yet it was still within Kiev Province.

See here: https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/community.php?usbgn=-1043201

If you suspect that “Chuskov” does not refer to the same town, then please refer me to some image of the writing, so I can have a better idea of how it is likely to be misspelled.

Yannay

Michael Levin

March 9, 2021

See the following map and the list of the most Jewish communities in Kiev province

https://map4us.com/MapViewer/1600556641580

Jill

March 12, 2021

I just re-found the records I am referring to, but I’m not sure how to insert a downloaded picture to this thread. I found the records through looking at WWI registration cards on familysearch.org; if I paste the url, it will just prompt you to sign in.

Yannay Spitzer

March 13, 2021

Jill, I think that you can just past the url, I should be able to log in and get there

Jill

March 13, 2021

I think you are right about Kashuwatt being Kivshovata! Here is the link for the record stating Chuskov. I guess it could be the same town, though this relative is from a different side of my family in no way related to the other relative, so that would be quite the coincidence. Thank you again for your help! https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-91V4-851?i=3020&cc=1968530&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AK6K9-2W1

Yannay Spitzer

March 14, 2021

So… I would also read it as “Chuskov”. But since it doesn’t seem to match with anything, my next guess would by Kharkov (spelled ‘Charkov’), which was outside the Pale of Settlement, but still had a sizeable Jewish community as well as a university that many Jews attended.

Yannay Spitzer

March 14, 2021

Alternatively, it could also be Zhashkov, also in Kiev province https://www.jewishgen.org/Communities/community.php?usbgn=-1060624

Jill

March 14, 2021

Thank you! I am just starting to get names of more of his relatives, so hopefully I will find more documents that match either of those locations or are nearby!